ADHD icon

His handwriting sucked ass wow

Poor Engels doesn’t get enough credit for having to edit all this shit. Imagine what the 3rd. volume of Kapital was like.

Jenny Marx also doesn’t get enough credit, she had to transcribe this stuff over and over

I’ve read that people with ADHD have awful handwriting, but I don’t know if that’s factual. I like to think mine isn’t so bad, but then again, I’m biased.

A lot of us do; dyspraxia and motor dysgraphia go hand-in-hand (pun not intended), and both are pretty common in people on the autism spectrum as well as with ADHD. My handwriting is fucking terrible and has been since I was a kid, to the point where I was often punished over getting poor penmanship grades on my elementary school report card.

Mine is trash and I have ADHD, while everyone elses in my family has nice handwriting.

His wife had to transcribe all of this

It’s a miracle anything got published

I always remember this sentence from the intro to vol 1 by Mandel: “The need to answer a sharp and slanderous attack by a German political opponent, a certain Herr Vogt, cost Marx nearly half a year’s delay in the production of Capital Volume 1.”

He was literally a 19th century redditor.

Half a year writing a diss track

I find it wild there’s like 3 books of Marx that Lenin never got a chance to read (this, Grundisse and the 1844 manuscripts).

Most of it didn’t, lol. Half of what we know of Marx are what he wrote for himself.

Genuinely what the fuck was going on in Marx’s mind. Why did he draw the same face hundreds of times on one page. Was he ok

Holy shit!

Maybe doodling helped him focus and concentrate

Could’ve been drunk too.

I was going to post the excerpt of the Police Report describing Marx’s unkempt home, but I think the whole report is worth reading anyway. I’ve taken this from a reddit comment, so beyond this point is the text of that comment:

I think this quote originates in English in Karl Marx: Interviews and Recollections, 1981, edited by David McLellan. Here’s the full excerpt, which was translated by McLellan from G. Mayer’s ‘Neue Beitrage zur Biographie von Karl Marx’, Archiv fur die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiter bewegung, 1922. It’s pretty LOL. McLellan introduces it like this: “This extract is the major part of a report from an anonymous German spy. It was probably written, at the bequest of the Prussian authorities in Berlin, in the autumn of 1852. At that time the Prussian Government was organising a show trial of communists- the onus for whose defence lay chiefly with Marx.”

The leader of this party is Karl Marx; his lieutenants are Engels in Manchester, where there are thousands of German workmen; Freiligrath and Wolff(known as Lupus) in London; Heine in Paris; Weydemeyer and Cluss in America; Burgers and Daniels were his lieutenants in Cologne, and Weerth in Hamburg. All the rest are merely Party members. The shaping and moving spirit, the real soul of the Party, is Marx; therefore I will go on to acquaint you with his personality.

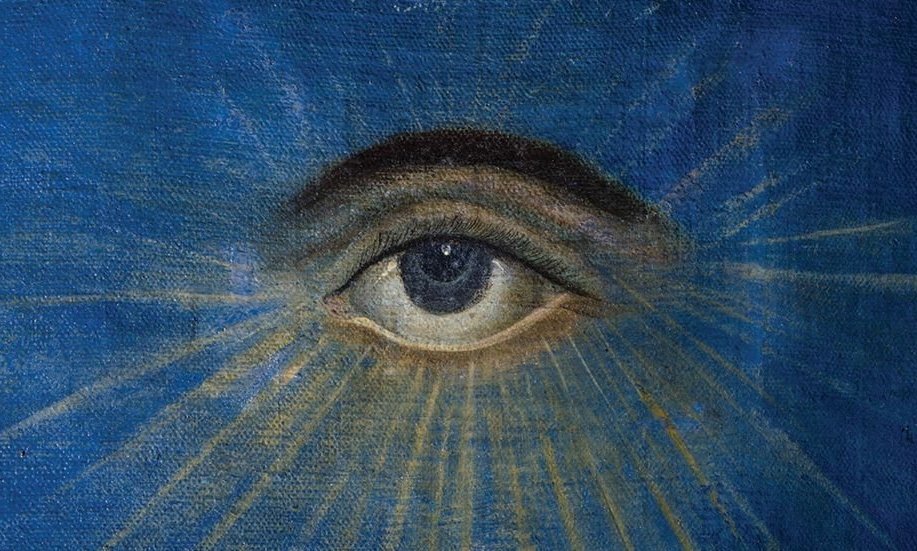

Marx is of medium height, thirty-four years old. Although in the prime of life, his hair is already turning grey. He is powerfully built, and his features remind you very distinctly of Szemere, only his complexion is darker, and his hair and beard quite black. The latter he does not shave at all. His large piercing fiery eyes have something demonically sinister about them. The first impression one receives is of a man of genius and energy. His intellectual superiority exercises an irresistible power on his surroundings.

In private life he is an extremely disorderly, cynical human being, and a bad host. He leads the existence of a real bohemian intellectual. Washing, grooming and changing his linen are things he does rarely, and he likes to get drunk. Though he is often idle for days on end, he will work day and night with tireless endurance when he has a great deal of work to do. He has no fixed times for going to sleep and waking up. He often stays up all night, and then lies down fully clothed on the sofa at midday and sleeps till evening, untroubled by the comings and goings of the whole world.

His wife is the sister of the Prussian Minister von Westphalen, a cultured and charming woman, who out of love for her husband has accustomed herself to his bohemian existence, and now feels perfectly at home in this poverty. She has two daughters and one son, and all three children are truly handsome.

As husband and father, Marx, in spite of his wild and restless character, is the gentlest and mildest of men. Marx lives in one of the worst - therefore, one of the cheapest - quarters of London. He occupies two rooms. The one looking out on the street is the living room, and the bedroom is at the back. In the whole apartment there is not one dean and solid piece of furniture. Everything is broken down,tattered and torn,with a half inch of dust over everything and the greatest disorder everywhere. In the middle of the living room there is a large old-fashioned table covered with an oilcloth, and on it there lie his manuscripts, books and newspapers, as well as the children’s toys, and rags and tatters of his wife’s sewing basket, several cups with broken rims, knives, forks, lamps, an inkpot, tumblers, Dutch day pipes, tobacco ash- in a word, everything topsy-turvy, and all on the same table. A seller of secondhand goods would be ashamed to give away such a remarkable collection of odds and ends.

When you enter Marx’s room, smoke from the coal and fumes from the tobacco make your eyes water so much that for a moment you seem to be groping about in a cavern, but gradually, as you grow accustomed to the fog, you can make out certain objects which distinguish themselves from the surrounding haze. Everything is dirty and covered with dust, so that to sit down becomes a thoroughly dangerous business. Here is a chair with only three legs, on another chair the children are playing at cooking- this chair happens to have four legs. This is the one which is offered to the visitor, but the children’s cooking has not been wiped away; and if you sit down, you risk a pair of trousers. But none of these things embarrass Marx or his wife. You are received in the most friendly way and cordially offered pipes and tobacco and whatever else there may happen to be; and eventually a spirited and agreeable conversation arises to make amends for the domestic deficiencies, thus making the discomfort tolerable. Finally you grow accustomed to the company, and find it interesting and original. This is a true picture of the family life of the communist chief Marx. Now I wish to discuss him as a politician and leader of a conspiracy.

As head and leader of a plot Marx is undoubtedly the most capable and well-suited man next to Mazzini, but when it comes to intrigues he is a worthy equal to the Small Roman. Marx is exceptionally cunning, crafty and reserved; he is difficult of access; on the other hand, he will support in every way and defend to the death anyone in whom he has once placed his trust. He will not admit that he could be mistaken in a man whom he had investigated. Marx is jealous of his authority as head of the Party; against his political rivals and opponents he is vengeful and implacable: he does not rest until he has destroyed them. His main quality is boundless ambition and lust for power. In spite of his programme of communist equality, he is the absolute ruler of his party. It is true that he does everything himself, but then only he commands and here he will brook no opposition. All this only concerns the secret workings and the secret sections; in open Party meetings, by contrast, he is the most liberal and popular of all.

He has depicted himself as the chad

Just like me fr

Are those the ghosts haunting europe on the right?

It’s the rough sketches for the manga. Marx knowing full well that it would be needed to educate the illiterate masses.

Theres an actual Communist Manifesto manga, but it’s an educational manga

He is just like me fr